Like the COVID-19 virus, polarisation is a product of our global interconnectedness. It also illuminates the disconnections in society – unequal access to power and wealth and the marginalisation and oppression of groups of people. Yet the pandemic has also stimulated great compassion, respect and solidarity. Restorative justice has evolved to address social disconnection by activating the positive qualities of humanity such as respect for human dignity and solidarity with others. Restorative Justice is an inclusive approach of addressing harm or the risk of harm through engaging all those affected in coming to a common understanding and agreement on how the harm or wrongdoing can be repaired, relationships maintained and justice achieved.

I come from Northern Ireland, a society deeply polarised by a conflict that has lasted centuries. The causes and nature of this conflict are contentious. Yet there may be a pattern which other countries can learn from. Polarisation between social groups is often linked to injustices. When parliamentary politics do not address these injustices, there will be protest which, if repressed or ignored, will escalate to violence. In Northern Ireland, many people died and many families have grieved and communities have been left with a legacy of injustice that continues to this day.

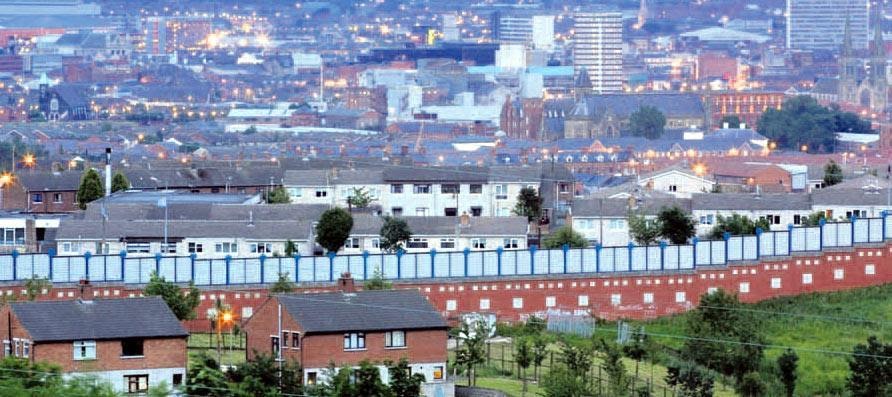

The restorative approach understands polarisation as a threat to the values of a cohesive, peaceful and democratic society. The separation of people can lead to seeing other groups as a risk to security or as competition for resources such as jobs and accommodation. In Belfast high walls have been built to create security between antagonistic communities. Yet such conditions nurture extremism and hatred. As the German-American political philosopher Hannah Arendt wrote: “Totalitarianism appeals to the very dangerous emotional needs of people who live in complete isolation and fear of one another.”

The restorative process does not see people as the problem. The problem is the harm caused by polarisation. The people from the polarised social groups are the resources for working towards the solution. Rather than keeping them apart, restorative processes bring people together in dialogue with a view to understanding the problem from all sides and to coming up with a way forward. When a hate crime occurs, the criminal justice system focuses on detection and prosecution and tries to exclude other parties from becoming involved. The restorative justice process includes all those affected and implicated in the harmful event. This includes the victims and those close to them and the perpetrators and those close to them.

The surrounding community may not only be victimised by the crime but also partly responsible for the harm. Bystanders who do nothing when harm occurs can be the source of greater hurt to the victim than the perpetrator. For Roberto Esposito, the Italian philosopher, community is not formed by a common identity or territory but by our obligations to each other. Polarised identities are “the perversion of the idea of community into its opposite, into one that erects walls rather than breaking them down.”

Restorative justice enables people to meet either to build community or to repair community after a harmful incident. This can be done through restorative circles or conferences in which everyone is supported to relate their experiences and express their feelings and views and to listen and question each other in a safe and respectful manner. A restorative circle is a non-hierarchical communication process in which each participant sits in a circle and speaks in turn without interruption.

The BRIDGE project plans to use theatre and video to engage marginalised young people in Val d’Oise (France) with a view to reducing the polarisation between them and the police. In Leuven (Belgium), the Mayor and various municipal, private and community-based organisations are developing the networks, strategies and processes to sustain a Restorative City. This initiative will serve to maintain social cohesion and to respond effectively to any social conflict which could exacerbate polarisation.

To summarise, restorative justice mitigates polarisation through building respect for human dignity, strengthening solidarity with and responsibility for others, undoing injustice and connecting people in dialogue.

Recommendations

The theory of restorative justice and the tool of restorative circles or conferences can be used by local authorities – with the involvement of relevant stakeholders – to counter structural inequalities and to mitigate polarisation.

Tim Chapman

A long-time Efus collaborator, Tim Chapman is a Visiting Professor at Università degli Studi di Sassari in Sardinia. Tim lectured at the University of Ulster in Northern Ireland, UK from 2002 to 2019 teaching on the Masters programme in Restorative Practices. He has contributed to the development of restorative justice practice in both the community and statutory sectors in Northern Ireland. He spent 25 years working in the Probation Service in Northern Ireland. He played an active part in developing effective probation practice in the UK particularly through the publication of Evidence Based Practice, written jointly with Michael Hough and published by the Home Office. His ‘Time to Grow’ model for the supervision of young people has influenced youth justice practices especially in Scotland. He has published widely on restorative justice and effective practice and has conducted significant research into restorative justice in Northern Ireland including the ALTERNATIVE project which focused on restorative justice and intercultural conflict. Two books have been recently published on this research. In 2015 he wrote with Maija Gellin and Monique Anderson A European Model of Restorative Justice with Children and Young People (International Juvenile Justice Observatory, IJJO). He is chair of the Board of the European Forum for Restorative Justice.