A student partnership project between the Sustainable Design School and the PACTESUR project

Nice, France, July 2021 – Since 2019, Laetitia Wolff, design impact consultant and instructor, has been leading a partnership-based course between the Sustainable Design School of Nice (SDS) and the PACTESUR project, in which Efus is a partner. The PACTESUR project commissioned the SDS to evaluate security equipment deployed in the project partner cities of Nice, Turin and Liège, as well as to create innovative security devices and strategies and to imagine ways to engage citizens in the process. In this PACTESUR publication, she explores the role of design in the protection of public spaces and the need to apply human-centered design approaches to security.

The role of the Sustainable Design School in the PACTESUR project

By Laetitia Wolff

One of the four pillars of the PACTESUR project is the identification of the most suitable local investment for securing open and touristic public spaces through the development of pilot security infrastructure, which can be transferred to other European cities. The Sustainable Design School of Nice (SDS) was called to evaluate the security equipment installed in the consortium’s partner cities: in Nice, the western segment of the Promenade des Anglais secured by bollards; in Turin, cameras and facial recognition software on Piazza di Veneto, and, in Liège, removable barriers set up on Saint Lambert square.

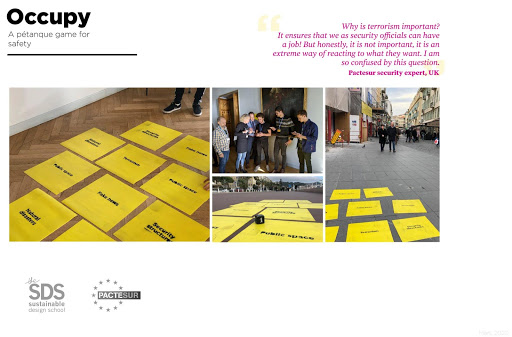

Leveraging my experience working with the New York Police Department (NYPD), and community-centered design work conducted for years in New York, I had the pleasure of leading this initiative coaching the talented students of the SDS over the past two years. Introducing an experimental action-research and a creative, human-centred design approach to security was probably the biggest leap for tech-driven security experts and municipal administrators. The partnership-based course, started with The Promenade des Anglais as the first site of study (2019-20). Taking the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal #11 as our compass – “to make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable”– our first student group entitled In/Pact devised interactive street interventions, board games and citizen engagement strategies. They questioned the traditional top down decision-making process in favour of a participatory approach to urban design, shifting perspectives by involving migrants in their user journey, and democratising the prickly, taboo topic of terrorism.

Launched earlier in 2021, in time of COVID, MIRO interactive board classes and overall Zoom life, the second chapter of our collaboration, entitled Project Citiz, invited students to focus on Turin’s Piazza Veneto and Liège’s Place Saint Lambert. With no travel possible, we conducted our research by interviewing a wide network of people – Belgian and Italian residents, architects, criminologists, designers, police force representatives, psychologists, prevention educators, and urban labs directors.

We aimed to explore how design could facilitate the integration of security devices, strategies and services into a larger context, whether in the urban landscape or in society. How do we avoid “bunkerization”? Should security be included in civic education, to become a preventive strategy vs. a curative process? Can security become a topic proactively and openly discussed amongst citizens and with the police? These are some of the questions that underpinned our discovery process until students arrived at a strategy of four complementary design solutions, organised around simple action verbs: Be informed, Notify, Act and Commit yourself. The solutions presented here include a prevention graphic intervention, an app, a warning bracelet and a shield-like barrier system for public events. For each of the design solutions proposed by students, we thought of anticipating the evaluation of impact so that municipal services and police forces would be equipped with an automatic feedback loop integrated in the new devices.

At a time when issues around securing public space, terrorist attacks, and police/citizen interactions sadly are part of our daily news, this most recent teaching experience has opened my eyes on the complexity of security. Most importantly it helped me realise how much the notion stands at the intersection of multiple dimensions – all equally meaningful – whether it’s about human needs, ethical values, democratic duties, urban life, environmental standards, or cultural values.

How do you see the role of design in the protection of public spaces? What are the obstacles to implementation?

Laetitia Wolff: If our intention is to secure urban public spaces while ensuring that they remain safe, open and accessible to all, the process ought to include human-centred design methods. Design shouldn’t be an afterthought or perceived as a luxury in protecting public spaces. Fundamentally based on human needs, communication, dialogue, and information sharing, design generates different kinds of solutions that engineering alone cannot produce.

Not only does design assert its capacity to respond to users’ needs, it also has this formidable power to bring together multiple points of view, foster transdisciplinary perspectives, know-how and professions, not letting the conversation in the hands of a single, vertical, technical expertise. Design has this potential to make security an everyday conversation topic. The main difficulty is to precisely take this time and process into account in what often seems to be a technical even technological decision that has to happen fast.

Do you think that the reflections provided by design are sufficiently integrated when installing equipment in public spaces?

The reflections that design provides are multi-dimensional: from understanding usage to defining the experience of a space, psychographic to symbolic, communication-related to programmatic. However, securitization equipment, because they respond to places and times of trauma, often seek quick, visible responses and are not thought out enough as an integrative part of a larger planning and citizen engagement strategy. Going back to design’s ability to translate human needs and its potential in integrating into a specific urban setting with heightened legibility we can advocate that design could be called earlier, upstream, to anticipate the use of new equipment.

One of the areas for reflection is the management of crowd behaviour and movements, what projects are you developing on this subject?

Students tried to look for solutions that would prevent the “tunnel vision” and the “arch phenomenon” that typically creates dangerous bottlenecks during panic attacks. They sought to devise security devices that would become instinctively recognisable, visible, and fluidify the movement of people to exit public spaces. Exploring sound and smell effects, water projections, visual codes, and particularly light as a medium for messaging and directing crowds in big event circumstances was at the heart of their early research.

They looked at light beams, ground-based light trails, colour-coded light portals to evacuate crowds, signal changes or indicate the closest exits. They thought of a universal graphic language and patterns that would facilitate crowd management and potentially be “attached” onto existing infrastructure. They ended up scaling down the light track to the human body by literally putting security in the hands of citizens to allow immediate signal. As a result, the Locate ME bracelet, most effective at night, will diffuse a smooth light in the crowd, when one of its two buttons is pressed. By creating a glare, an issue in a crowd can be immediately geolocated, inducing a faster reaction for law enforcement.

We found the idea of “protective furniture” very interesting, the design of street furniture that could be used for hiding during a possible attack. Could you tell us more?

In the existing typology of street furniture, security devices and event management, there is a hodgepodge of solutions that are often ‘collaged’ to create a barrier – it doesn’t look good, doesn’t say “secure and safe” nor does it facilitate the work of municipal services and law enforcement.

The Shield Us barriers proposed by SDS students simplify the current security devices (“blackout panels”) and create a more standardised typology of objects that can also provide a communication surface. Foldable and easy to stock, the barriers are simple in the way they are installed, easing the time spent preparing a delimited event area. As they are adjustable, they can be disposed to break any rectangular angle in an event, responding to the “arch phenomenon”, therefore fluidifying a potential evacuation.

You also explore the idea of rebuilding “coveillance” through a sense of social cohesion. Could you give us an example in terms of urban public spaces?

Coveillance is a concept that borrows from psycho-sociology work done thirty years ago in Canada, and has taken a new meaning in relation to ubiquitous surveillance, civil liberties, urban hack. It means to be attentive to the needs of the other; in fact, less of a concept than a state of mind, it’s “doing together” what cannot be done alone, in a dynamic of building social bonds.

Inform is one of the modules devised for the Project Citiz by SDS students to sensitize citizens about security tips, behaviours, new policy and simple actions, through a playful and accessible graphic marking on the ground. Ephemeral and dynamic information brings prevention at your feet, literally, and shows citizens they can be actors of their own security. Walk the talk.

What recommendations would you give to local authorities wishing to install safety equipment in their public spaces?

First adopt an open, transdisciplinary, cross-sector approach to the understanding of the problem, not top down, not just tech, not expert only. Think of public space as a canvas that’s never completely white or neutral. Start with understanding the context and take into account all of it: physical site specs, recent history, background stories, trauma, cultural identity and iconic markers that make it a memorable space. Observe how people use the space today before thinking of adding equipment tomorrow – perhaps the answer is to subtract devices, urban furniture and structures to increase its legibility rather than add some. Secondly, think with an integrated strategy in mind: Is the physical barrier completed with an app? Is temporary or permanent signage a pendant to lighting treatment? Can we learn from event-driven devices to implement more permanent solutions and induce collective behaviour? Finally, safety equipment should be thought out as part of larger considerations integrated into urban design, street life, tourism destinations, cultural representation; overall the goal should be to entice citizens’ appropriation of cities.

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of Efus. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.

About the author

Laetitia Wolff is a design consultant, cultural engineering strategist, curator and author with a passion for building bridges between design and the city. She has also launched design + social justice programmes and led creative placemaking projects, focusing on societal issues-urban gentrification, racism, the role of women, public safety, and ecological transition. Since 2019, she has been leading a partnership-based course between the Sustainable Design School of Nice (SDS) and the PACTESUR project, introducing an experimental action-research and a creative, human-centred design approach to security.

(www.laetitiawolff.design; https://www.designville.co/)

Special thanks to the SDS students who participated in In/pact and Project Citiz projects, Grant Linscott, academic director and Maurille Larivière, SDS director.

In/pact – Part 1 (2019-20)

SDS student designers: Mathieu Andries, Holly L. Bartley, Maxime Chef, Julian Coiffard, Enzo Jamois, Tarushee Mehra, Sacha Nouviale, Arjun Rao, Fanny Ricciardi, Matthew Slack, Stefani Takac, Tristan Terrusse, Nicolas Thomas, Agatha Verlay.

Project Citiz – Part 2 (2021)

SDS student designers: Jules Baudrand, Ibrahim Benouna, Owen Cartau, Juliette Dunand, Romain Desrez, Marine Jean, Lola Mangot, Pauline Poirot, Clément Pheulpin, Noémie Rocheteau, Manon Roulant, Baptise Viot, Emma Weber, Eva Zortich.

About PACTESUR

The PACTESUR project aims to empower cities and local actors in the field of security of urban public spaces facing threats, such as terrorist attacks. Through a bottom-up approach, the project gathers local decision makers, security forces, urban security experts, urban planners, IT developers, trainers, front-line practitioners, designers and others in order to shape new European local policies to secure public spaces against terrorist attacks.

About the PUBLICATION SERIES

A partner in the PACTESUR project, Efus is publishing a series of articles written by the project’s Associated Cities and Expert Advisory Committee, with the aim of contributing to the European debate on the protection of public spaces against threats. Because the security challenges affecting public spaces are in constant evolution, this collection intends to be a space for reflection and discussion on these issues.